Solemn Chapter of the Nativity

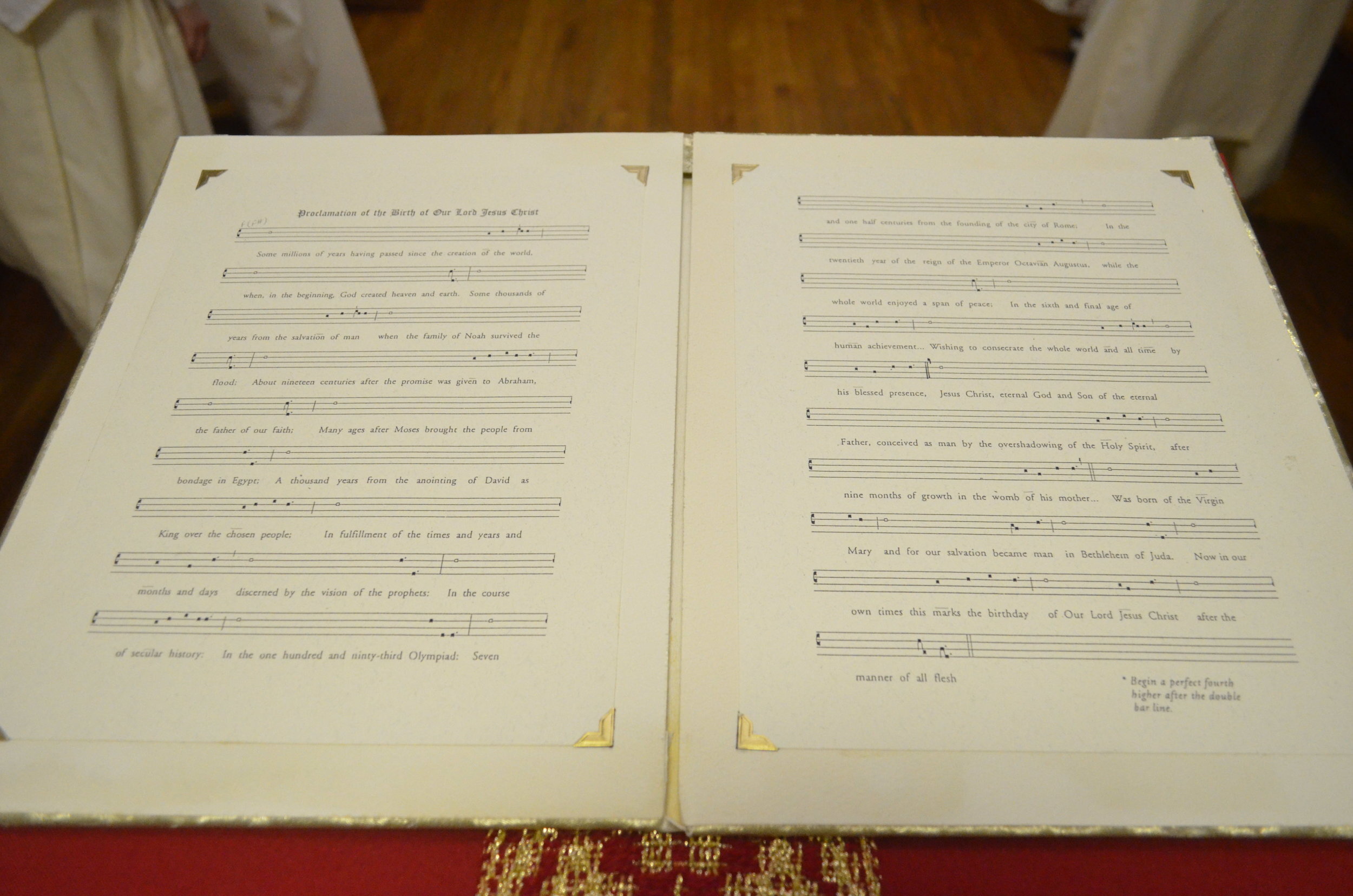

This morning the community gathered in the Chapter Hall after Mass for Solemn Chapter. All stood as Sr. Joseph Maria chanted the proclamation of the Birth of Christ.

Following the Proclamation the venia is made and then Sr. Mary Martin invites the sister who will be giving the homily up. This is always kept secret, so no one knows which sister it will be until she stands up (if the sister is a novice the novice mistress knows, of course). This year Sr. Chiara Marie was chosen to give the homily (which you can read below!) and did an amazing job!

Sr. Chiara Marie's Homily:

Sisters, I hope you will forgive this slightly unconventional beginning but, being still so new to this life I struggled to know where to start. So, I decided to borrow the words of the poet Patrick Kavanagh who’s words are far more eloquent then mine.

Advent by Patrick Kavanagh

We have tested and tasted too much, lover-

Through a chink too wide there comes in no wonder.

But here in this Advent-darkened room

Where the dry black bread and sugarless tea

Of penance will charm back the luxury

Of a child’s soul, we’ll return to Doom

The knowledge we stole but could not use.

And the newness that was in every stale thing

When we looked at it as children: the spirit-shocking

Wonder in a black slanting Ulster hill

Of the prophetic astonishment in the tedious talking

Of an old fool will awake for us and bring

You and me to the yard gate to watch the whins

And the bog-holes, cart-tracks, old stables where Time begins.

O after Christmas we’ll have no need to go searching

For the difference that sets an old phrase burning –

We’ll hear it in the whispered argument of a churning

Or in the streets where the village boys are lurching.

And we’ll hear it among decent men too

Who barrow dung in gardens under trees

Wherever life pours ordinary plenty.

Won’t we be rich, my love and I, and please

God we won’t ask for reason’s payment,

The why of heart-breaking strangeness in dreeping hedges

Nor analyse God’s breath in common statement.

We have thrown into the dust-bin the clay-minted wages

Of pleasure, knowledge and the conscious hour –

And Christ comes with a January flower.

I first encountered the poetry of Patrick Kavanagh when I was sixteen. The first two lines and the last have stayed with me ever since. He may never have reached the dizzying literary heights of fame enjoyed by W.B. Yeats but he is considered one of Ireland’s best loved poets. During his life he battled alcoholism and in this poem his longing for a return to innocence is laid bare.

Jesus tells us that unless we become like little children we cannot enter the Kingdom of Heaven. But how can this be achieved? There is no reversal of time. Over and over we repeat the sin of Adam and Eve, reaching for knowledge and experience that we neither need nor is good for us. When glimpsed through the narrow chink sin takes on a seductive glamour and as the serpent said to Eve he says to us to take, to taste and never mind what God may say. Once we reach out its appeal quickly turns to dross and we are left wounded through our own fault. The wonder disappears and innocence is tarnished, if not lost.

During Advent we do not sit in a darkened room (except when praying the rosary in choir) and while we do not restrict ourselves to black bread and sugarless tea we do fast and keep watch. Penance, regret and a humble request to God to heal our wounds helps to purify us. God allows us to throw away the clay-minted wages through the Sacrament of Confession and the Eucharist. But something more is needed. To see the wonder of our lives through a child’s eyes we need to open ourselves up to trust, both in God and our neighbor. But the knocks of life generally teaches us to do the opposite.

Some would say that this is prudent. If someone hurts you why would you let them do so again? But what about God? I have heard many people say, with apparent justification, if God is such a just, loving God then why does he allow evil in the world. How do we keep on trusting through the bad times when experience tells us to hoist up our barricades? I believe through grace and prayer we can open ourselves up to God and become like children again.

Children, especially very young ones love with their whole being and throw themselves with confidence at the ones they love. Generally the first thing I would encounter at my best friend’s house is my name being screamed and three giggling bodies wrapping themselves around my legs, waist and hurtling themselves into my arms, sometimes from the stairs. They loved me, therefore they trusted I would catch them.

I have a dim memory, no doubt boosted by my mother’s retelling of the story, of her carrying me up to the altar rail. When she knelt down to receive the Eucharist I yelled ‘Mine!’ and tried to take it from the priest’s hand. When my mother said no I screamed ‘My Jesus, mine!’ I wish I could claim some deep theological insight but at that stage in my development everything I saw was ‘Mine!’ And yet, I believe that on some level I recognized that Jesus was truly present, that the One my mother told me was my best friend was in the Host.

Complete trust in God, I believe is the key to returning to a childhood (without the screaming tantrums) state, to born again in innocence. As I listen to the Advent readings and sing the ‘O’ antiphons I experience a deep thrill inside me, like I’m a child again on Christmas Eve night waiting for Santa Claus to come. Except this time it is the Christ Child coming with His January flower.

Every Christmas Eve my mother would put a candle (usually an electric one) in the window to welcome the Holy Family in, to let Them know that there was room for them in our home. Later I learnt the other meaning of the custom. During the penal times, when Catholics were persecuted in Ireland the lit candle in the window was to tell any travelling priests out in the cold that it was safe to knock on the door.

Trust in God kept the Catholic faith alive in Ireland during the two hundred years of persecution. People wore their rosaries as a bracelet and carried crucifixes with short arms that could be quickly shoved up sleeves if the soldiers came by. Very few people could read so children were catechized using the rosary and simple rhymes with hidden meanings. Their parents brought them out to the hedge schools held in the open fields.

Any who felt the call to religious life or the priesthood had to be smuggled out of Ireland to France or Spain. Those who returned faced an almost certain cruel martyrdom. Priests were regarded as traitors to the king or queen of England and as such were hung, drawn and quartered. I will spare you the details of what this meant.

Yet hundreds of priests and religious did return though it meant a life constantly on the run. Mass was celebrated in the middle of the night in lonely places. Rocks formed the altars and to this day there are still some of these Mass rocks preserved. The Blessed Sacrament at Knock is exposed in a carved out hollow of one such stone as a reminder to us of the persecutions.

On one occasion a priest was celebrating Mass on a mountainside while several men kept watch for the soldiers. People came from miles around. It could well be months before they would be able to attend Mass again. As the priest elevated the Host the word came, the soldiers were on their way. The people begged the priest to leave but he refused to go until he finished celebrating Mass.

Afterwards he lingered, perhaps to baptize a child or to hear confessions. Again the people begged him to go, no priest, no sacraments. Finally he threw off his robes and not stopping to pick them up he ran. The soldiers were almost there. A man from the ragtag congregation picked up the robes and put them on. When the soldiers came he held out his hands in surrender and said ‘I am the priest’. He was dragged off to a cruel death. Only a deep, abiding trust in God could give ordinary people the courage to face the persecutions and continue to hand on the Faith.

St. Oliver Plunkett was an Irish man who lived seventeenth century. He had been ordained first a priest and then a bishop in Rome. He taught in one of the seminaries and had by all accounts a comfortable, orderly life. Then the request came, would he go back to Ireland and minister to the people? They had had no bishop for over fifty years. He agreed without hesitation.. He was made Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of all Ireland and in the middle of the night he was smuggled into Ireland.

For several years he managed to evade the soldiers. Among other things he offered the sacrament of Confirmation to hundreds of people in fields and on mountain sides. He also helped to set up the hedge schools which lasted up until the 19th century to educate children for free. Eventually he was caught, brought to Tyburn in London and after torture and a mock trial was executed. His last words are reported to be ‘I desire to be dissolved and to be with Christ’. His head was displayed a pike close by. Today, close to the site of the executions of so many martyrs is a cloistered community of Benedictine nuns who have perpetual adoration of the Blessed Sacrament (the actual site is in the middle of the street).

Some of St. Oliver’s friends managed to take back his body and his niece was given his skull. When she entered the Dominican Monastery of St. Catherine of Siena in Drogheda she brought it with her.

The sisters have frequently called on the intercession of St. Oliver Plunkett and St. Joseph to protect their monastery. They managed some semblance of monastic life and ran a boarding school for girls which was their excuse for living together in community. The prioress at the time was a woman from a rich, noble family and had some standing in the town. One night, the soldiers came while they were praying Compline. The Prioress changed quickly and went to answer the door while the other sisters prayed for help.

‘Madame, are the women living here nuns?’ asked their leader.

‘My dear sir, they are no more nuns then I am.’ She stood in the doorway and stared them down. The soldiers went away. This was not their only narrow escape but they survived, most monasteries did not.

Becoming children without becoming childish, a return to innocence and seeing the wonder of God in everything. Advent is a time for sloughing off the polluted dregs of the world and prepare, not for the coming of Santa Claus but the coming of Christ, in the manger and in our hearts. May God grant us all a peaceful and blessed Christmas.