Lent in the Monastery

Lent.

A time for prayer. A time for penance. A time for seeking the Lord more deeply, more wholeheartedly. As creatures of body and soul, our outward practices foster the environment necessary for the inward conversion of heart that God asks of us when he says: “Return to me with your whole heart, with fasting, weeping, and mourning. Rend your hearts, not your garments, and return to the Lord, your God, for he is gracious and merciful, slow to anger, abounding in steadfast love, and relenting in punishment.” (Joel 2:12-13)

Into the desert with Christ

The Gospel reading on the first Sunday of Lent speaks of Jesus going out to the desert where he prays and fasts for 40 days. While the monastery is itself already a going into the wilderness to be alone with the Lord, Lent is a time when we seek that solitude with Christ more deeply. We refrain from writing, calling, or visiting with family or friends. Communications with the outside world are limited to what is necessary to keep the monastery going, or what charity demands.

On Friday nights, instead of gathering together for recreation in the evening, we instead in solitude seek the Lord in prayer and contemplation. Some sisters use this time to pray the Stations of the Cross. Others spend it with the Beloved in the solitude of their cells or with his Eucharistic presence in choir.

But when the Bridegroom departs, then they will fast.

From ancient times fasting has been a primary means of asceticism - a discipline of the body that conforms the soul to God. David turns in repentance to fasting when the prophet Nathan confronts him with his sin. When Jonah preaches imminent destruction - “40 days more and Nineveh will be destroyed” - the people responded with repentance, proclaiming a fast extending even to their animals. When Esther prepares to speak to the King on behalf of her Jewish people, she asks them to join her in fasting for three days, asking God to be with her.

Fasting conveys many things - repentance for sin, requests for God’s mercy and help, or simply the worship of God. In fasting, I say to God, “I want you more than anything else - more than this food that I hunger for.” Fasting is such an appropriate response to sin because sin says the opposite: “I want this more than I want you, God.” We are creatures of habit, of dispositions formed in us by repeated choices. Fasting trains our soul into the habit of choosing God no matter what. In this way, it not only conveys my sorrow for sin, but is actually its remedy.

In the monastery, we fast and abstain from meat during the Lenten season, breaking the fast (but not the abstinence!) only on Sundays. When my stomach rumbles and images of delicious forbidden delicacies float uninvited across my mind, I am reminded that I should hunger for God, the true food of my soul, just as much as my body hungers for sustenance.

Like any form of penitence, fasting is not a matter of proving to God (or even to myself) just how tough I can be. It is something I embark on in humility, knowing my weakness, but knowing that God will support me and carry me through, giving the grace that is both my work and its reward.

Lent in the liturgy

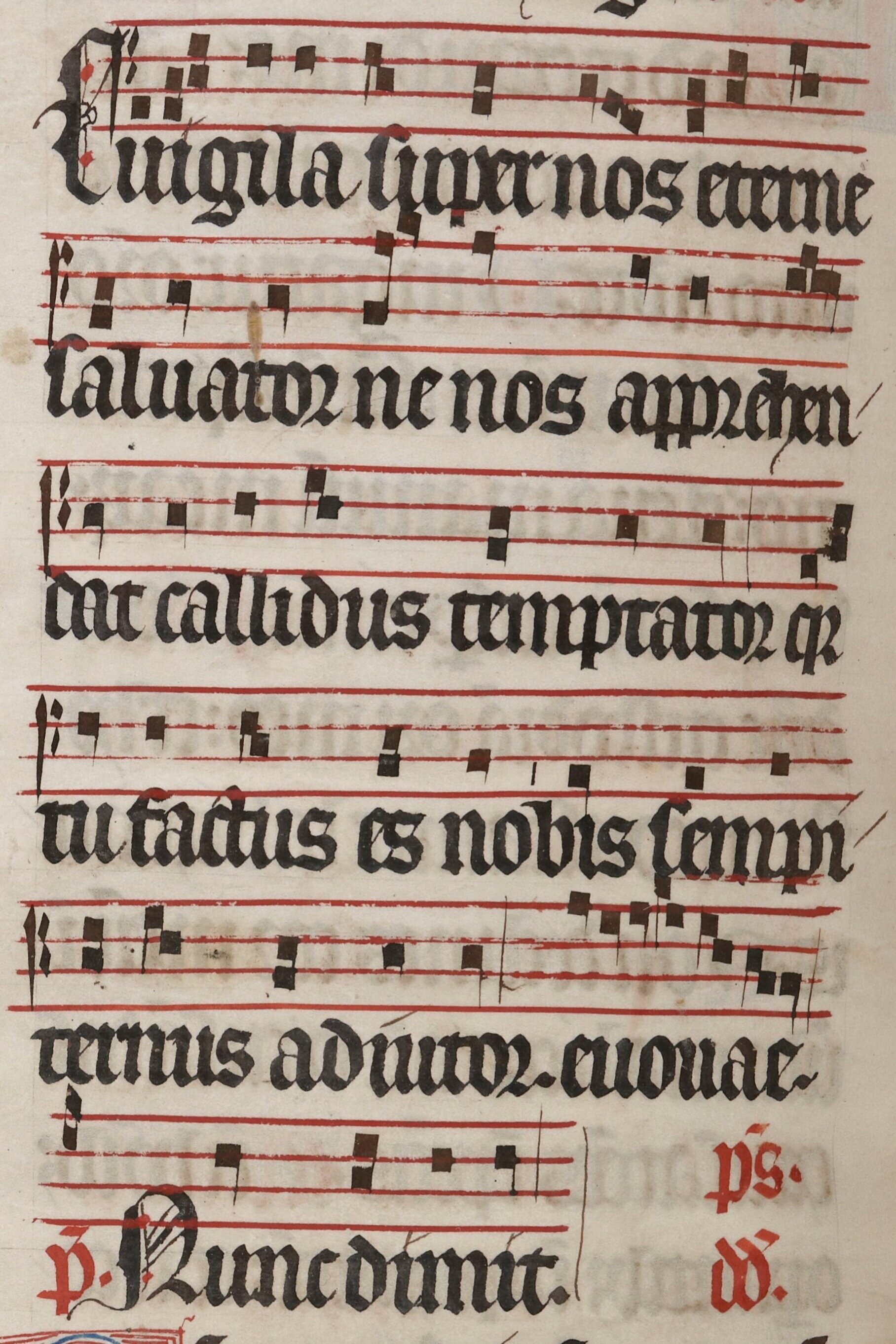

An image of a manuscript c.1300 with the antiphon “Evigila” which we sing at Compline in Lent. “Watch over us, eternal savior, lest the cunning tempter apprehend us. For you have been made an eternal helper for us.”

Many of our customs in the liturgy of Lent speak to these themes of prayer and penitence. The “Alleluia” normally appended to the Glory Be which opens the office is suppressed. Certain intonations and psalms which would ordinarily be accompanied by the organ are instead sung against the stark backdrop of silence. I feel more insecure singing alone - the little imperfections of my voice, a slightly off-pitch note, are no longer covered by the accompanying organ. This brings to me an image of how my soul is meant to be in this season: brought out into the light of God, not hiding behind my images of what I want to be, but in humility facing my own failings so that they can be healed by a loving God.

At the conclusion of the hours of the Office, we kneel during the intercessions at Lauds and Vespers and for the concluding prayer of each hour. The psalms and readings themselves continually bring out themes of repentance, of sorrow for sin. In the Office of Readings, we follow the story of the Passover and Exodus from Egypt, foreshadowing our own journey to the true promised land. As Lent progresses onward, the realization that our penitence is founded in the mystery of Christ’s passion becomes ever clearer. Many of the psalms and readings contain foreshadowings from the Old Covenant of the coming Messiah. This reaches its climax in Holy Week, when all attention is turned fully towards participating in the Lord’s Passion.

After the office of Midday Prayer on Fridays, we turn towards the altar, kneeling, and outstretch our arms in the form of a crucifix. Singing the following words, we intercede before God: “Spare O Lord, spare your people. Be not angry with us forever.” On alternating Fridays, we sing the same text in Latin: “Parce Domine, parce populo tuo. Ne in aeternum irascaris nobis.” This always reminds me of the reading from one of the Little Hours of the office, from the prophet Joel: “Between the porch and the altar, let the priests, the ministers of God, weep and say: ‘Spare, O Lord, your people, and do not make your heritage a reproach, with the nations ruling over us.’” (Joel 2:17) Every Christian shares in the priesthood of Christ by virtue of our baptism, and as nuns we enter into the intercessory role of this priesthood in a special way.

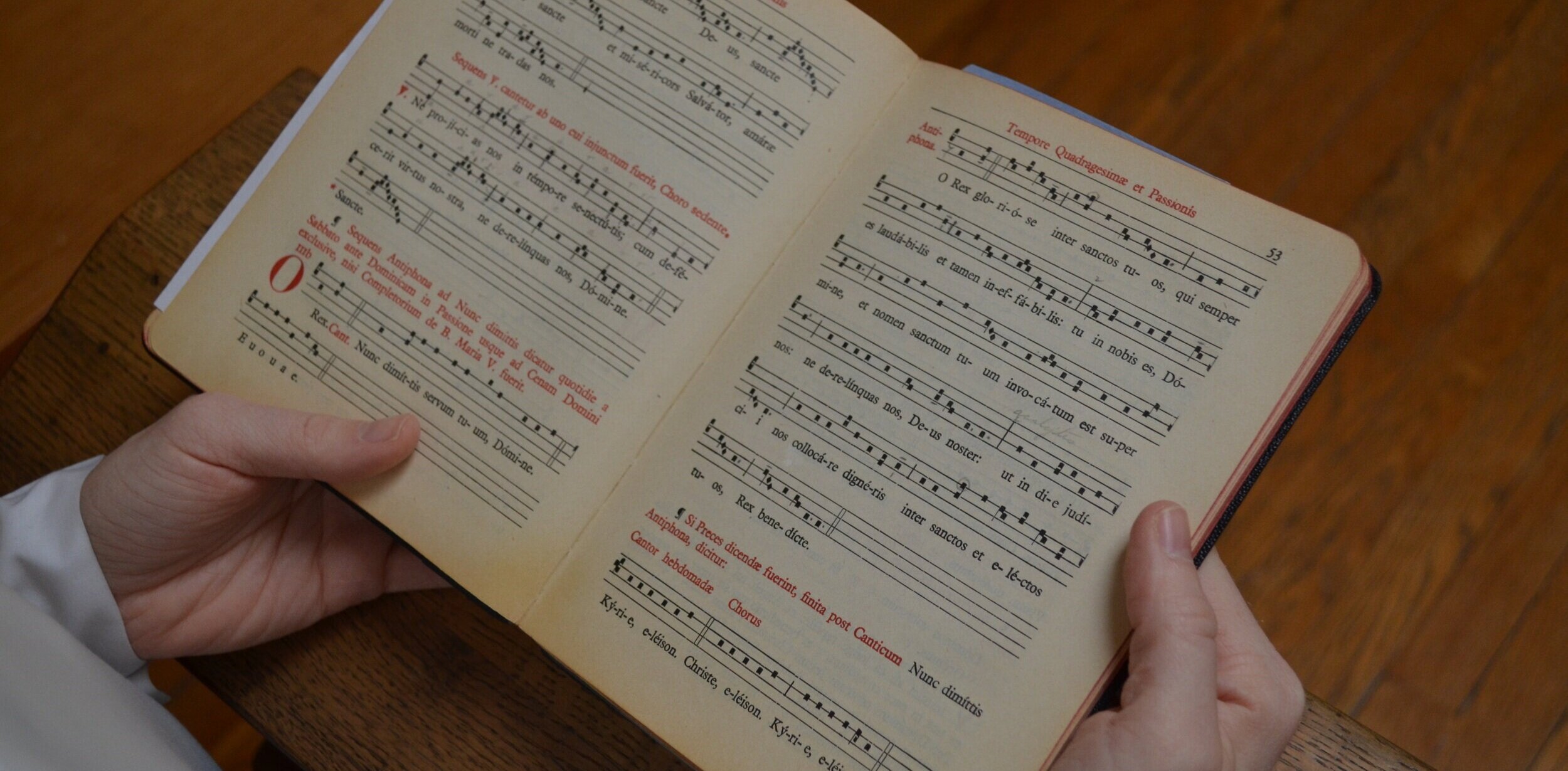

At the office of Compline, the last prayers of the day before we retire for the night, we sing some of the Latin responsories and antiphons from the old Dominican Office, continuing the liturgical tradition of chants that the Order has sung for 800 years. This is one of my favorite parts of the Lenten season. There is just something about hearing those flowing chants which speaks to the soul.

“O Rex gloriose inter sanctos tuos, qui semper es laudabilis et tamen ineffabilis: tu in nobis es, Domine, et nomen sanctum tuum invocatum est super nos: ne derelinquas nos, Deus noster: ut in die judicii nos collocare digneris inter sanctos et electos tuos, Rex benedicte.”

The texts themselves are beautiful as well. Take, for example, the antiphon “O Rex”, which is sung as the Nunc Dimittis antiphon during the last two weeks of Lent. It translates: “O King, glorious among your saints, who are always praiseworthy and yet ineffable: you are in us, Lord, and your holy name has been invoked over us: do not forsake us, our God: that on the day of judgment you might consider us worthy to place us among your saints and elect, O blessed King.” What a beautiful prayer: the image of our Lord as praiseworthy and yet unable to be contained by our praises, already present in us but yet we still long for the fullness of his presence among the saints in heaven. How blessed we are to have received this rich liturgical heritage!